Yesterday the once highly respected New York City law firm Paul Weiss announced that it had entered into an agreement with the White House for the withdrawal of an Executive Order directed at the firm. In some ways a rehash of the EO against Perkins Coie, but in some ways worse, I was expecting this EO to be enjoined on similar grounds – as an effort to intimidate law firms from advocating positions that the President, in his sole and unreviewable judgment, regards as “destroying bedrock American principles” or “activities that are not aligned with American interests.” (That language is from the EO aimed at Paul Weiss, not a report of the House Un-American Activities Committee from the 1950s.) I expected Paul Weiss to put up a fight and stand up for the independence of the legal profession and the rule of law.

Not a chance. They caved. For a very brief moment I thought it might be a shrewd diplomatic move, where they agreed to some anodyne statement of professional values to give Trump a way to back down without looking like he had lost. (David Noll posted on Bluesky that he had a similar initial reaction.) That, of course, would have been by far the less preferred outcome from the point of view of the independence of the legal profession and the maintenance of the constitutional order. The right thing to do would have been what Perkins Coie did, by retaining a highly skilled and courageous law firm to file a lawsuit demonstrating the eight ways it’s unconstitutional (for review: beyond the scope of presidential authority, violation of procedural due process, void for vagueness, denial of equal protection, political viewpoint discrimination, compelled disclosure, retaliation for engaging in protected activities, and denial of right to counsel). The legal action almost certainly would have been successful, and two big law firms pushing back on these flagrantly unconstitutional executive orders might have given heart to other law firms that worry about getting crosswise with the administration.

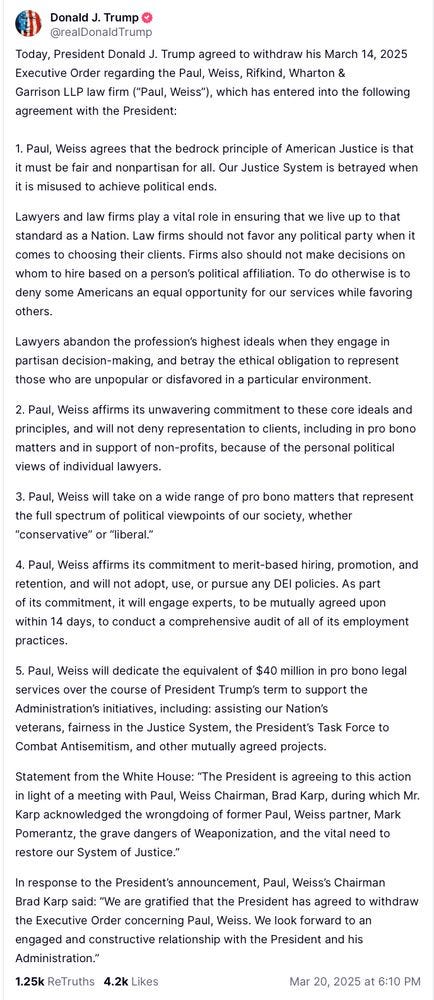

Instead we got this gloating Truth Social post from Donald Trump, announcing that Paul Weiss had bent the knee:

The death of irony has been proclaimed for a long time, but as an example it is difficult to top the first paragraph, in which Donald Trump piously proclaims that our justice system is betrayed when it is misused to achieve political ends. This from a guy who has been famous for decades – long before his involvement in politics – for abusing litigation for his personal and business ends. Since becoming president the first time, Trump has engaged in a striking pattern of using defamation and other civil lawsuits to intimidate critics. And one of the big stories in the news last month was the attempt by Emil Bove, then Acting Deputy Attorney General, to dismiss criminal charges against NYC Mayor Eric Adams, as a way of securing his cooperation with the administration’s deportation strategy.

Even worse, from my perspective as a legal ethics scholar, is the upside-down invocation of core professional ideals and principles to justify surrendering to an authoritarian leader. Brad Karp, the chairman of Paul Weiss, reportedly sent an email to firm employees stating that he had merely reaffirmed a set of principles stated in 1963 by one of the firm’s founding partners. You be the judge of whether you think the terms of the agreement between the firm and Trump would be consistent with the ethical principles that a law firm should affirm. The statement recites the following ideals and commitments made by the firm as part of the deal, which I’ll annotate for the benefit of readers who are confused by a law firm’s invocation of them to justify playing ball with the Trump Administration:

“Justice . . . must be fair and nonpartisan for all.” True, “justice” must be fair and nonpartisan. That’s a core underlying value of judicial ethics. But the word “partisan” here is doing a lot of work. Big law firms famously tend to represent powerful corporate interests. The most cursory Google search turns up the following list of Paul Weiss clients: Amazon, Apollo Global Management, Bain Capital, [huge Australian mining company] BHP Billiton, the Carlyle Group, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, Kraft Heinz, Intel, Mastercard, McDonald’s, Merck, Morgan Stanley, SAP, Starbucks, and Viacom. To be clear, I think this is fine. A law firm can specialize in areas like takeover defense, corporate governance, capital markets, or white collar criminal investigations. If it does so, it’s going to end up being on one side or the other of contested social and political issues. This has always been the case, which is why many of my students make a big show out of claiming that they only want to work at a large law firm for a few years, pay off their student loans, and then go work in the public interest. It’s also why firms put so much effort into touting their pro bono representation in civil rights, capital post-conviction, and similar types of litigation. If you see this, however, you can see how menacing it is that Trump’s EO declared that Paul Weiss, among other large firms, is engaging in activities “inconsistent with the interests of the United States.” That’s straight-up authoritarianism, not a political critique of big law firms as representing powerful corporations. I’m not naïve about power, and understand that concentrated private power can be a threat to liberty, too. However, as a constitutional. matter, which is what we are talking about here, there is a fundamental distinction between state and private power.

“Lawyers and law firms play a vital role in ensuring that we live up to that standard as a Nation.” Very true, which is why lawyers – and particularly the organized, elite bar – has always emphasized the bedrock value if independence. In order for justice to be fair and impartial, it is essential that lawyers be free to challenge the exercise of state power. This is one of the bases for the frequently repeated (and, in my view, misunderstood) nonaccountability principle, that lawyers should not be identified with their clients’ views. The joint Trump-Paul Weiss statement seems to have in mind the criticism by left-leaning observers of law firms representing firearms manufacturers, fossil fuel companies, companies like Amazon and Starbucks that resist unionization by workers, and so on. If the right objects to this, however, the response is to make the case for professional independence and the importance of representing all clients, not to bring a major law firm to heel and insist that it represent only Trump-aligned clients.

“Lawyers abandon the profession’s highest ideals when they engage in partisan decisionmaking.” Really? Does Trump feel the same way about Jones Day, which reportedly built close ties to the first Trump Administration? Come to think of it, does that observation extend to Paul Weiss’s commitment to spend $40 million supporting pro bono representation “to support the Administration’s initiatives”? There has been a longstanding meme on the right that big law firm partners are a bunch of woke Marxists. Apart from the observation above that big law firm clients tend to be financial services institutions, insurance companies, manufacturers, and the like, the data simply don’t bear out that claim. Other than certain sub-groups like plaintiffs’ personal-injury and mass tort lawyers, the pattern of campaign contributions to Democratic and Republican candidates tends to be fairly similar. Anyone who has worked at a big law firm knows that they are comprised of lawyers with a huge diversity of political viewpoints. If there is any unifying force in a big law firm it is the emphasis on financial performance, as described in a recent book: Mitt Regan & Lisa H. Rohrer, BigLaw: Money and Meaning in the Modern Law Firm (University of Chicago Press 2021). It is a cliché in the legal profession literature that the rise of the American Lawyer magazine kicked off the era of obsessing over the metric of profits per partner, greatly increased lateral mobility, law firm mergers and bankruptcies, creation of non-equity partner tracks, and other concessions to the fact that big law firms are big business. The idea that big law firms engage in partisan, as opposed to profit-driven, decisionmaking is something that only someone who has never spent much time around big law firms would believe.

“Lawyers abandon the profession’s highest ideals when they . . . betray the ethical obligation to represent those who are unpopular or disfavored in a particular environment.” At the risk of rehashing what I wrote recently, I agree that there is something valuable about representing unpopular clients, and that lawyers rightly understand that as part of a great professional tradition. But this statement seems to be right out of Trump’s grievance playbook if he somehow understands the results of the 2024 election as evidence that the Republican Party is “unpopular or disfavored.” Right now, the officially disfavored positions and clients can be determined by looking at the list of executive orders issued by the Trump Administration, targeted at immigrants (the invocation of the AEA and the attempt to deport Mahmoud Khalil), green energy (the asset freeze directed at funds disbursed by the EPA in the last months of the Biden Administration), transgender people generally and armed service members in particular, international human rights and humanitarian aid (the dismantling of USAID), and government employees.

“Paul Weiss . . . will not deny representation to clients, including in pro bono matters and in support of nonprofits, because of the personal political views of individual lawyers.” Lawyers have almost complete discretion to decide which clients to represent. That’s true in pro bono representation as well as paid engagements. It has never been the case that the personal political views of an individual lawyer would be a reason for the firm not to undertake a representation. Even if a lawyer’s personal political views are so strongly held that they would materially limit the lawyer’s ability to represent a client, and thus create a conflict of interest under Model Rule 1.7(a)(2), that conflict is not imputed to other lawyers in the firm under Model Rule 1.10(a)(1). Very few lawyers in a large firm are sufficiently influential that their personal political views or objections to taking on a specific client would make a difference to the firm’s decisionmaking. (Unfortunately an associate at Skadden Arps is about to learn that lesson, having sent an email around the firm urging it to do something to protest Paul Weiss’s surrender. More recent reporting suggests that her email account was frozen by the firm.)

“Paul Weiss will take on a wide variety of pro bono matters that represent the full spectrum of political viewpoints of our society . . ..” Immediately contradicted by a more specific commitment to dedicate the equivalent of $40 million to pro bono services “over the course of President Trump’s term to support the Administration’s initiatives.”

The ABA and 50 other bar associations issued the following statement today: https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/aba-news-archives/2025/03/bar-organizations-statement-in-support-of-rule-of-law/?utm_source=sfmc&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&promo=&RefId=&utm_id=988866&sfmc_id=50726630

Another excellent piece by Mr. Wendel. However, while “A Disgraceful Capitulation” is certainly true, “Cowardice Comes to Law Firms” might be more direct and to the point. But any way you cut it, this is a sad commentary on the profession. I thought Perkins Coie set the standard in terms of responding to Trump’s Executive Order attempting to put it out of business (which Paul Weiss chose to ignore), and I hoped maybe most of the lawyers who had capitulated were already working for the Trump administration in one federal agency or another. Wrong—and likely naïve.

It seems to me that courage is the key ingredient missing in many responses to the Trump administration’s assault on the country, perhaps most notoriously in some law firms. But courage is also in short supply in other areas of practice. Judges need more courage to recommend disciplinary charges against attorneys bringing insincere—and even dishonest—arguments to the court room. A highly visible and reported case is that of Judge John Coughenour who recently upbraided Justice Department attorneys in open court for bringing the “blatantly unconstitutional” birthright citizenship case before him. Despite his harsh words for those attorneys, to my knowledge there is no evidence that disciplinary action has been or will be initiated against them. Mr. Wendel has previously addressed some of the reasons for the frequent failure to advance disciplinary charges, but it remains a defect in the profession. And, of course, attorneys need more courage to refuse to make specious arguments, whether of their own accord or in response to orders on high; hopefully, there are many cases of refusal to “follow orders” than the highly publicized resignations of a few Department of Justice attorneys.

Finally, it is also a sad commentary on the profession, and big firms in particular, when it is the associates of firms who are joining together to voice their objection to capitulation to Trump’s Executive Orders. But the good news is that those folks are tomorrow’s firm managers who will, hopefully, bring their idealism and moral strength with them.